Obsessed with the idea that the Indian people of the Pacific Northwest would soon follow her into extinction, Curtis began traveling to nearby native communities to preserve something of them for history.

“He hoped to convey a face that had seen worlds change, forests leveled, tidelands filled, people crushed.”Ĭurtis got his picture.

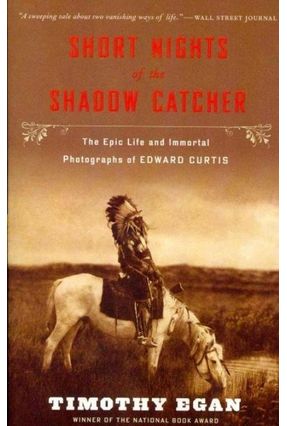

“He was looking for the lethal glare she saved for the boys who threw rocks at her,” Egan writes. Curtis worked days to capture the portrait he wanted, an encounter between photographer and subject that Egan describes with his own patience and skill. “Princess Angeline” was then 100 years old. Then he decided to photograph the impoverished woman famous locally as the last surviving child of Chief Seattle. It soon became clear he had “the eye,” and within four years he was Seattle’s most renowned photographer, shooting portraits of its wealthiest citizens. From a traveler headed to Alaska’s gold fields, he bought a 14-by-17-inch view camera.Ĭurtis set up a photo studio. In and near Seattle, Curtis literally earned his living from the muck: digging for clams and doing other menial jobs. The man behind these images was the son of a humble Minnesota family who resettled in Seattle during that city’s late-19th century transformation from frontier town to Western metropolis. And his photograph of the tragically regal Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce, covered in shell necklaces just months before a death his doctor attributed to “a broken heart.” There is his 1905 portrait of the great Apache fighter Geronimo, with his weathered face. His portraits, especially, have a timeless quality.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)